The Caravan has published yet another of its very excellent mini-novel grade stories. This time around the Operation Blue star by Hartosh Singh Bal. For someone who was but a child in the times covered by this story, this was an enlightening read and I recommend you read it, since I’m not going to be summarizing the story here at all. I am no authority on the history or politics of Punjab. This post is about linkages and patterns I see beyond the story – which are also more perceptions than referenced fact.

Several things struck me about the story that I think have a deep insight for India’s politics as well.

The first was the role of the Congress government in the build up of religious extremism to the point of instability and largely for reasons of political gain for the party rather than the well being of citizens. It isn’t unlike what is going on with the rise of the Hindu right wing in India, with the Congress making vague comments about alarm or criticism, but never really doing anything to strike a solid blow, to the point its leaders could be publicly humiliated and party decimated this elections.

That tendency to cater to the most violent representatives of a religion (Muslim zealots included) rather than defuse aggression and uplift the masses at large seems to be alive and well to the point where the claims of secularism fell flat. This time, it seems few bought the idea that tolerating zealots of all hues is secularism and a rogue right wing ran away with the narrative. Not unlike what it sounds like from the Punjab of those days, except perhaps the violence is now uniformly perpetrated against the unarmed.

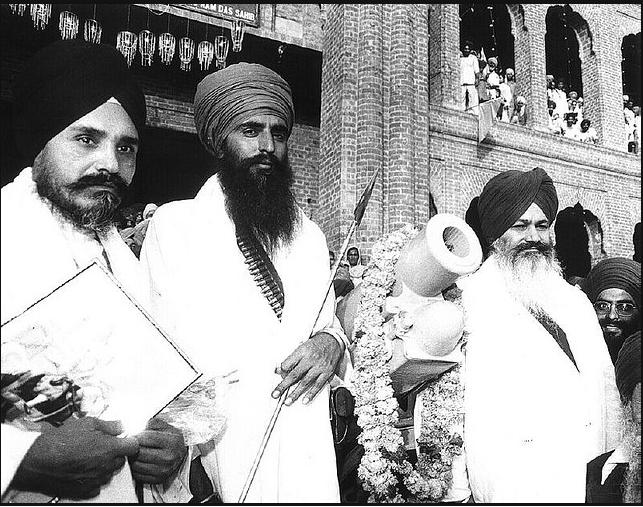

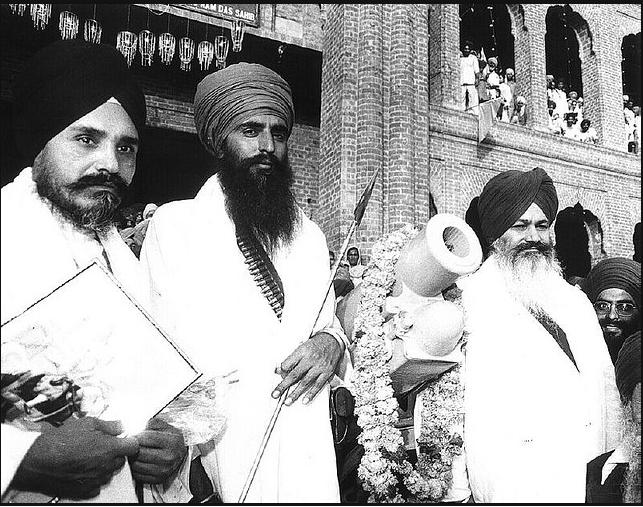

The massive following of Bhindranwale in the face of criminal acts, impotence of the state machinery to deliver justice or regain control and more too sounds like a recurring theme for India.

Short sighted strategies for political gain with little view for the impact on the larger picture? Yep.

The inability of the state to control rogues within the security establishment as well continues with encounter killings being covered up rather than brought to justice.

Bad advisers, bloodthirsty youth leaders and a leadership unable to see beyond what was presented? Yep. Leadership regretted? Yes. Leadership paid heavy price? Yes. Bad over reactions to a long nurtured problem created martyrs opposing state?

In some ways the cult like following of Bhindranwale reminds me of Bal Thackeray. The man who got a state funeral after a life of taking the law in his hands at whim. In our area, the Bahujan Vikas Aghadi rules. This party is unheard of in most of India. Founded by a local don with a murder to his name, and sporting an MLA who thrashed a cop in the Assembly, the bling of the Lok Sabha Election campaigning didn’t touch our area. No posters, no mega rallies, no vans blaring messages. Perhaps they may have happened nearer the station, but not here. Our area was completely Modi free, even when the BJP candidate won – some celebrations probably happened in more central areas, but I didn’t hear any fireworks sitting at home. Yet when Bal Thackeray died, his posters were splashed all over and again for the anniversary. They remained up long after the date had passed.

When it comes to love of the masses, clearly sentiment trumps law – something a state insensitive to people is ill equipped to deal with.

What was the charisma of the law breaker? Identity. Bal Thackeray may have done little to improve the lot of Maharashtrians, but in a state where the natives feel increasingly marginalized, he gave their frustrations voice, even if he did nothing very useful with it. His political affiliations too were courted, not unlike Bhindranwale.

And in Punjab, it seems every other car sports stickers in honor of the “dreaded separatist terrorist” and the BJP that is normally vociferous against terrorists and had indeed supported his killing meekly falls in line, just like Bal Thackeray’s political opponents respectfully attended his funeral, even as they worried whether his party will continue to squat over the Shivaji Park and demand a memorial there.

In hindsight. I wonder if Bhindranwale’s “evil” was not the violence, but the Anandpur Resolution. After all, India is a country with a rich history of might not only being right, but being rewarded with more might. On the other hand, all calls for decentralization and redistribution of power would hardly have induced cheer in the hearts of those wanting to use him as a puppet for political profit.

In many ways, the story of Operation Bluestar is still a story of India without the outright “Gangs of Waseypur” effects. What has the state learned? It is unclear.

The Bhindranwale legend continues to grow even though Bhai Mokham Singh has renounced the gun. It is clearly about identity more than legality or lack thereof. The mistrust of the central government continues to manifest in many ways, even when there remains no serious militancy anymore. In a Punjab reeling under the toll of drugs, “restoration” of many youth from alcohol and drugs takes on significance of its own. In 2003, at a function arranged by the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee, Joginder Singh Vedanti, former jathedar of the Akal Takht made a formal declaration that Bhindranwale was a “martyr” and awarded his son, Ishar Singh, a robe of honour.

But perhaps the most fascinating for me was the last page. After losing a generation to the militancy and on the verge of losing another to drugs (or is it already lost?), what resonated in my mind was that the extent of political marginalization of the Sikhs could be expressed with one mind boggling fact.

The United Sikh Movement led by Bhai Mohkam Singh of Damdami Taksal announced to support the Aam Aadmi Party this January – partly due to the Aam Aadmi Party constituting a SIT to finally probe the 30 year old anti-Sikh riots. The only four seats Aam Aadmi Party got out of over 400 seats nationwide are from Punjab.

And the magnitude of support that this had among the people can only be measured by the fact that the BJP, usually happy to accuse AAP of supporting terrorists did not so much as whisper about the support of United Sikh Movement to AAP. They simply cannot afford to go against the legend when BJP supporters claiming Sikhs to be Hindu in a recent Twitter spat were asked by a Sikh to ask Akali Dal to repeat it in Punjab if they dare.

And I am left wondering about how history gets written. What becomes about religion, when religion becomes a tool for harvesting power, what transcends that purpose to become about survival of identity, when religion serves as an umbrella for deeper rifts in trust and how we, as a remarkably diverse country can hope to bridge differences if we don’t learn from our past.

Is it possible to divorce politics from religion in a country where religion is not only interwoven with people’s lives, but the traditions have roots in governing people? What is an acceptable line? What cannot be compromised for religion? Are the lines the same for all religions, or different? How can the parts that must not bend to religion be enacted without alienating people? Is it really such a big problem, or is it a problem created by a style of politics long used to exploiting religion as an easy means of harvesting support of people?

Strangely, it reminds me of Kashmir’s anger over Afzal Guru, who at best was a flunky in the attack on the Indian Parliament. He had evidently quit the separatist movement as well and by no means was any hotshot hero for Kashmiris before his arrest – quite different from the already iconic SANT Bhindranwale, but managed to become the symbol of irreconcilable differences for the identity at large, way beyond the issue that put him on the wrong side of the state.

It keeps coming back to fault lines of razor wire that those in power nurture and each time, the reason appears to be political opportunism.

It is strange that our history of diversity and numerous experiences with communal fault lines has not yet led us to attempt responses that are measured and in the interests of people. Cater to exploit, crush to conquer. How long can we go on like this? When do we start healing?

In a speech at the Kanadi Sahitya Academy on the occasion of his works being translated to Kannada, Marathi playwright, author and polymath Pu La Deshpande had said that Maharashtra and Karnataka share a border, but Maharashtrians and Kannadigas share a confluence. Decades later, India is desperately in need of minds that see more confluences than borders.